Difference between revisions of "The Theory of Rationales"

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

If you understand why Jones hit Smith, then you have an explanation for the claim “Jones hit Smith.” Specifically, you know what caused Jones to hit Smith. Notice that when you explain some conclusion, you do not doubt the truth of the conclusion. You are trying to understand how the conclusion came about or why it is the case. | If you understand why Jones hit Smith, then you have an explanation for the claim “Jones hit Smith.” Specifically, you know what caused Jones to hit Smith. Notice that when you explain some conclusion, you do not doubt the truth of the conclusion. You are trying to understand how the conclusion came about or why it is the case. | ||

| − | + | To summarize, a rationale is any reason – conclusion relationship in which reasons imply a conclusion. Reasons or premises can imply a conclusion by giving us a basis for accepting the truth of the conclusion on the basis of some evidence or by helping us understand a conclusion. In the first case, we have an argument and in the second case, we have an explanation. In this model, explanations are causal. They always involve an assumption that we understand something if we understand how it comes about and what it is related to. Everything related to appreciating the significance or “meaning” of things can then be thought of as “interpretation,” a crucial, but distinct activity from explaining. Both arguments and explanations are types of rationales. | |

| + | |||

| + | This is the core of the theory of rationales which Dr. Randy Mayes, a philosopher of science at California State University at Sacramento, has developed in a number of articles’ and talks. While the idea of a “warrant” or rationale for a conclusion is basic to logic since before the ancient Greeks, the elegance of the “Theory of Rationales” is that it shows the relationship between arguments and explanations in a particularly clear way, something that traditional logic has had some difficulty doing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The theory of rationales is not just a good conceptual map of the main types of rationales. It also directs us toward some practical skills, particularly the skill of recognizing when someone is offering an argument and when they are offering an explanation. Argumentative and explanatory aims are found separately and together in deliberative reflection. Since each rationale raises different questions for response, you will be in a better position to engage in reflection if you can distinguish types of rationales. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using an example from Mayes’ work, consider the following two statements: | ||

| + | Spot is scared of the mailman. The mailman terrorizes Spot. | ||

| + | Which of these is the premise and which is the conclusion? Well, it depends upon whether you see the implication between them as argumentative or explanatory. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:ArgExpDirection.jpg|center|400px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the first case, construed as an argument, the implication arrow points to the right. Spot’s fear of the mailman might be a basis (evidence, really) for accepting the truth of the claim that the mailman terrorizes him. Of course, this isn’t “proof.” Spot could just be a neurotic territorial dog. But it is a rationale for believing in the truth of the conclusion about the mailman. In the second case, when we think about Spot being afraid of the mailman as a fact, the possibility that the mailman terrorizes Spot becomes a causal explanation for Spot’s condition. In this case, there is no doubt about the fact that Spot is afraid, we just want to understand why. In examples like this, in which the direction of implication and type of rationale can be changed together, you can’t even tell what claim is being supported without distinguishing arguments from explanations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To review and perhaps take another perspective, rationales are just implication relationships between some set of ideas | ||

| + | (expressed in sentences) and another. In this case, to keep things simple, we are just using one idea and relating it to another. Not all implication relationships are this easy to reverse. The direction of the implication between two claims often depends upon the context of communication. You can imagine two different contexts for the two kinds of rationales about Spot. In one, Spot’s owners suspect that the mailman is sadistic, but they are not sure. They are looking for justification. In the other, they are worried about poor Spot’s emotional health. They are trying to understand why he’s scared. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In our previous example about Jones and Smith, we said that the fact that a trusted friend witnessed Jones hitting Smith was justification for believing that the event really happened. Let’s vary that example to show how the event could be part of an argumentative or explanatory rationale. Suppose it’s been widely known that Smith was trying to win the affections of Jones’ girlfriend and that Jones is known to be a jealous and potentially violent person. Knowing all of this, the fact that Jones hit Smith could be explained by the hypothesis that Smith had finally succeeded. Or, if you already knew that Smith had won her heart, that could help you explain why he got hit or even predict that he will get hit! | ||

| + | |||

| + | The key to understanding the kind of rationale you are looking at is to ask yourself whether you are trying to establish the truth of a claim you are unsure about or whether you are trying to understand something you already know to be the case. If it is the first, you are justifying a belief and the rationale is an argument. If it is the second, you are trying to understand a fact and the rationale you offer is an explanation. | ||

Revision as of 19:16, 21 July 2008

The “theory of rationales,” which forms the centerpiece of our approach to argumentation in this book, gives us yet more new “reflective moves” to make in practical arguments. But like many theories it requires us to look a bit more closely at everyday phenomena – in this case, our uses of terms like “implies,” ‘reason,” “explanation,” and other terms.

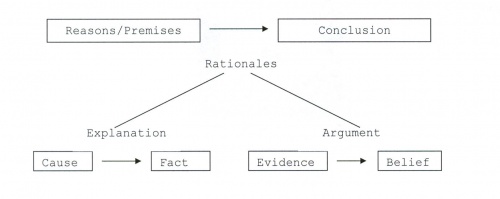

Reflection is ultimately about living better by getting our ideas connected in the right ways so that our thinking can guide our action. We can make a start on organizing our ideas by recognizing that ideas are often connected by the distinct roles they play. Just as some uses of language give us examples. Questions, facts, opinions, etc., others give us clues to what kind of reason is being given and how we might talk about the reasoning in a deliberation. For example, a claim is a statement about the world that is either true or false. Claims become conclusions of a thought process when we think we have support for them. The support for a conclusion is a premise or reason. The “support’ relationship is what we mean, in the most general sense, by implication. Whenever we draw a conclusion or make an inference reflectively we are employing this premise/conclusion structure. A rationale is any set of premises or reasons which imply a conclusion when the truth of those premises is somehow a basis for accepting or understanding the conclusion. In short order we’ve introduced six semi-technical terms: claim, conclusions, premise, reason,’ rationale, implication. Now we need to provide some elaboration on each.

What does it mean to “accept” a conclusion as true? Accepting a claim on the basis of some support for it means that you regard the support as a justification for behaving that the claim is true. Sometime the support comes from your own direct senses. In that case we would say the support is empirical fact. Support can also come from other sources, such as: reasoning about facts. Indirect knowledge through reliable accounts, and theoretical knowledge. For example, suppose the claim is, “Jones hit Smith in the bar near campus last night.” If I had not been there, I might be in doubt about the truth of this claim. But if a trusted friend said, “I was there and saw Jones hit Smith,” that would probably be enough evidence for accepting the claim as true.

In cases of justification or argument, we are considering a claim that is doubt. Everyone is talking about whether Jones really hit Smith. Some people think it happened, some don’t, others are unsure. In this case, a trustworthy eyewitness (or a video camera recording) can really help settle the question. But a justification for behaving that Jones hit Smith is not the same as understanding why Jones hit Smith. One half of our definition of a rationale was about inferences that justified claims, but the other half was about implications that helped us understand conclusions. In our example, knowing whether to believe that Jones hit Smith is one question; understanding why he did it is another.

If you understand why Jones hit Smith, then you have an explanation for the claim “Jones hit Smith.” Specifically, you know what caused Jones to hit Smith. Notice that when you explain some conclusion, you do not doubt the truth of the conclusion. You are trying to understand how the conclusion came about or why it is the case.

To summarize, a rationale is any reason – conclusion relationship in which reasons imply a conclusion. Reasons or premises can imply a conclusion by giving us a basis for accepting the truth of the conclusion on the basis of some evidence or by helping us understand a conclusion. In the first case, we have an argument and in the second case, we have an explanation. In this model, explanations are causal. They always involve an assumption that we understand something if we understand how it comes about and what it is related to. Everything related to appreciating the significance or “meaning” of things can then be thought of as “interpretation,” a crucial, but distinct activity from explaining. Both arguments and explanations are types of rationales.

This is the core of the theory of rationales which Dr. Randy Mayes, a philosopher of science at California State University at Sacramento, has developed in a number of articles’ and talks. While the idea of a “warrant” or rationale for a conclusion is basic to logic since before the ancient Greeks, the elegance of the “Theory of Rationales” is that it shows the relationship between arguments and explanations in a particularly clear way, something that traditional logic has had some difficulty doing.

The theory of rationales is not just a good conceptual map of the main types of rationales. It also directs us toward some practical skills, particularly the skill of recognizing when someone is offering an argument and when they are offering an explanation. Argumentative and explanatory aims are found separately and together in deliberative reflection. Since each rationale raises different questions for response, you will be in a better position to engage in reflection if you can distinguish types of rationales.

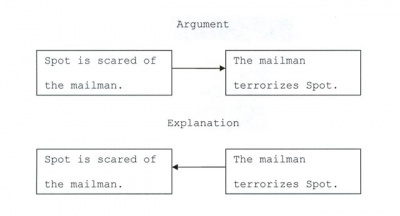

Using an example from Mayes’ work, consider the following two statements: Spot is scared of the mailman. The mailman terrorizes Spot. Which of these is the premise and which is the conclusion? Well, it depends upon whether you see the implication between them as argumentative or explanatory.

In the first case, construed as an argument, the implication arrow points to the right. Spot’s fear of the mailman might be a basis (evidence, really) for accepting the truth of the claim that the mailman terrorizes him. Of course, this isn’t “proof.” Spot could just be a neurotic territorial dog. But it is a rationale for believing in the truth of the conclusion about the mailman. In the second case, when we think about Spot being afraid of the mailman as a fact, the possibility that the mailman terrorizes Spot becomes a causal explanation for Spot’s condition. In this case, there is no doubt about the fact that Spot is afraid, we just want to understand why. In examples like this, in which the direction of implication and type of rationale can be changed together, you can’t even tell what claim is being supported without distinguishing arguments from explanations.

To review and perhaps take another perspective, rationales are just implication relationships between some set of ideas (expressed in sentences) and another. In this case, to keep things simple, we are just using one idea and relating it to another. Not all implication relationships are this easy to reverse. The direction of the implication between two claims often depends upon the context of communication. You can imagine two different contexts for the two kinds of rationales about Spot. In one, Spot’s owners suspect that the mailman is sadistic, but they are not sure. They are looking for justification. In the other, they are worried about poor Spot’s emotional health. They are trying to understand why he’s scared.

In our previous example about Jones and Smith, we said that the fact that a trusted friend witnessed Jones hitting Smith was justification for believing that the event really happened. Let’s vary that example to show how the event could be part of an argumentative or explanatory rationale. Suppose it’s been widely known that Smith was trying to win the affections of Jones’ girlfriend and that Jones is known to be a jealous and potentially violent person. Knowing all of this, the fact that Jones hit Smith could be explained by the hypothesis that Smith had finally succeeded. Or, if you already knew that Smith had won her heart, that could help you explain why he got hit or even predict that he will get hit!

The key to understanding the kind of rationale you are looking at is to ask yourself whether you are trying to establish the truth of a claim you are unsure about or whether you are trying to understand something you already know to be the case. If it is the first, you are justifying a belief and the rationale is an argument. If it is the second, you are trying to understand a fact and the rationale you offer is an explanation.