The Theory of Rationales

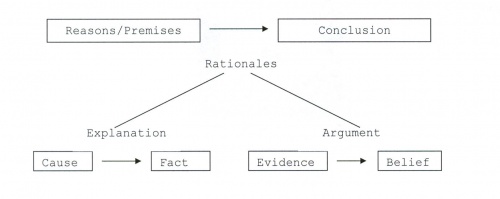

The “theory of rationales,” which forms the centerpiece of our approach to argumentation in this book, gives us yet more new “reflective moves” to make in practical arguments. But like many theories it requires us to look a bit more closely at everyday phenomena – in this case, our uses of terms like “implies,” ‘reason,” “explanation,” and other terms. Reflection is ultimately about living better by getting our ideas connected in the right ways so that our thinking can guide our action. We can make a start on organizing our ideas by recognizing that ideas are often connected by the distinct roles they play. Just as some uses of language give us examples. Questions, facts, opinions, etc., others give us clues to what kind of reason is being given and how we might talk about the reasoning in a deliberation. For example, a claim is a statement about the world that is either true or false. Claims become conclusions of a thought process when we think we have support for them. The support for a conclusion is a premise or reason. The “support’ relationship is what we mean, in the most general sense, by implication. Whenever we draw a conclusion or make an inference reflectively we are employing this premise/conclusion structure. A rationale is any set of premises or reasons which imply a conclusion when the truth of those premises is somehow a basis for accepting or understanding the conclusion. In short order we’ve introduced six semi-technical terms: claim, conclusions, premise, reason,’ rationale, implication. Now we need to provide some elaboration on each. What does it mean to “accept” a conclusion as true? Accepting a claim on the basis of some support for it means that you regard the support as a justification for behaving that the claim is true. Sometime the support comes from your own direct senses. In that case we would say the support is empirical fact. Support can also come from other sources, such as: reasoning about facts. Indirect knowledge through reliable accounts, and theoretical knowledge. For example, suppose the claim is, “Jones hit Smith in the bar near campus last night.” If I had not been there, I might be in doubt about the truth of this claim. But if a trusted friend said, “I was there and saw Jones hit Smith,” that would probably be enough evidence for accepting the claim as true. In cases of justification or argument, we are considering a claim that is doubt. Everyone is talking about whether Jones really hit Smith. Some people think it happened, some don’t, others are unsure. In this case, a trustworthy eyewitness (or a video camera recording) can really help settle the question. But a justification for behaving that Jones hit Smith is not the same as understanding why Jones hit Smith. One half of our definition of a rationale was about inferences that justified claims, but the other half was about implications that helped us understand conclusions. In our example, knowing whether to believe that Jones hit Smith is one question; understanding why he did it is another. If you understand why Jones hit Smith, then you have an explanation for the claim “Jones hit Smith.” Specifically, you know what caused Jones to hit Smith. Notice that when you explain some conclusion, you do not doubt the truth of the conclusion. You are trying to understand how the conclusion came about or why it is the case. The chart at the top of this document summarizes the basic “Theory of Rationales” we have been explicating.